By Mike Christensen, Utah Rail Passengers Association Executive Director

The railroads (and transportation in general) have always had a history of direct or indirect government subsidies in one form or another. For example, the federal government incentivized the building of the Transcontinental Railroad by giving Union Pacific and Central Pacific huge amounts of land along the rail corridors. Those subsidies came with expectations, including the operation of passenger trains.

As time went by and other transportation modes—particularly automobiles and airplanes—came along, national priorities changed and so did transportation funding. By the end of World War II, federal subsidies had shifted to highways and airports. Regrettably, we did not continue to invest in rail infrastructure like our peers in Europe and Asian did. For example, California is struggling to build a high-speed rail system that could and should have been built 50 years ago, if we had followed our peers’ example.

Despite the shift in national priorities, the governmental obligation of the nation’s private railroads to operate passenger service continued. Because of the heavily-subsidized highways and airports, the railroads struggled to compete and were losing money on passenger service. The railroads would often employ sneaky tactics in order discourage riders and thereby justify discontinuing routes to the government. Some of these tactics included dropping on-board services and replacing trains with buses. I mention this as it will become relevant later on.

In 1970, the railroads were successful in getting Congress to pass the Rail Passenger Service Act, which relieved the railroads of the obligation of running passenger service and created the National Railroad Passenger Corporation (Amtrak). “In return for relief from the burden of passenger service, the participating railroads were required to give Amtrak rights of access to their networks and agreed to an avoidable-cost formula for track-use charges.” In other words, freight railroads are required to provide reasonable access for Amtrak trains to use their tracks at a reasonable price. While Amtrak is technically a private company, it is wholly-owned by the federal government and is subject to Congressional oversight.

Amtrak is often unfairly viewed as an example of government waste because of the annual subsidy needed to continue its operation. However, in an act akin to the pot calling the kettle black, critics ridicule Amtrak, while completely disregarding the massive subsidies needed to support highways and air travel. The federal government provides more highway funding in one year than Amtrak has received in its entire 47-year history, yet critics continue to question why Amtrak struggles. Some see Amtrak as the biggest failure of American transportation, but I view it as the greatest success story in American transportation, since it rolls along despite being significantly underfunded. Amtrak now transports more than 30 million passengers per year, which, when compared to the number of domestic passengers transported by US airlines, makes Amtrak the fifth largest airline. As a side note, I just stumbled upon a New Yorker article titled “If Amtrak Were An Airline,” which further sheds light on Amtrak’s advantages over airlines.

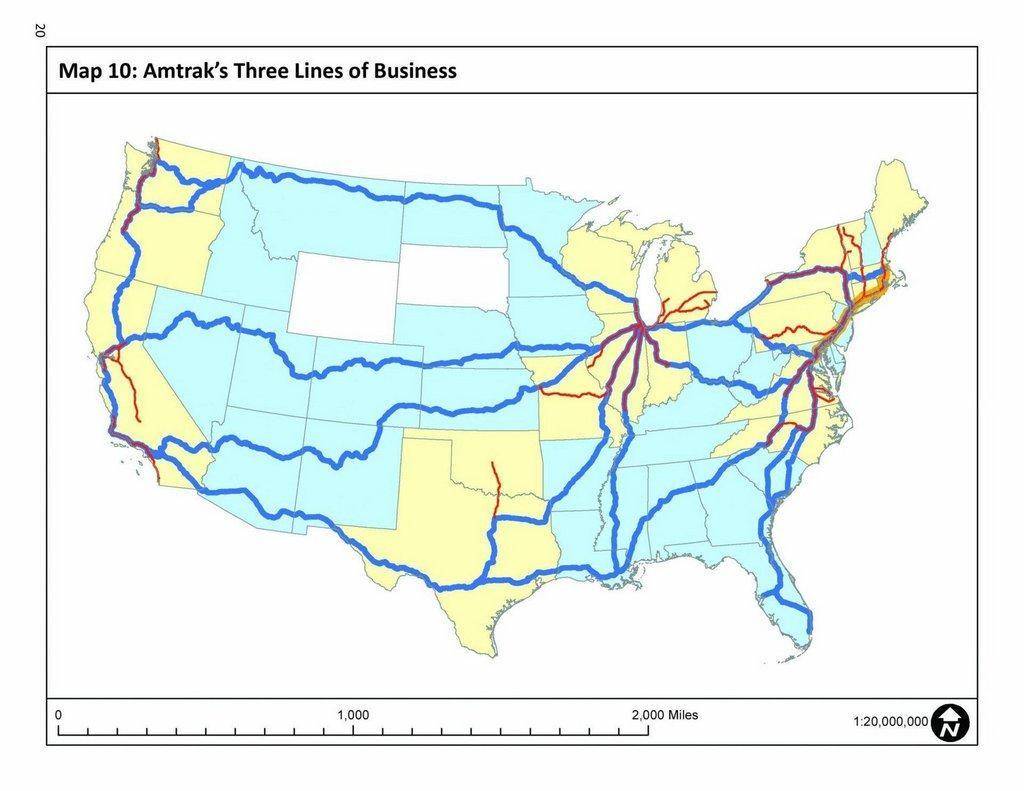

The above image maps the Amtrak system broken down by the three lines of business. The Northeast Corridor is highlighted in gold, long-distance routes are in blue, and state-sponsored routes are in red. States lacking Amtrak service are in white, states with Amtrak service are in blue, and states with Amtrak service that also sponsor routes are in yellow. In terms of 2017 ridership, the Northeast Corridor transported more than 12 million passengers, state-sponsored trains transported almost 15 million passengers, and long-distance trains transported almost five million passengers. Average trip lengths were 164 miles for the Northeast Corridor, 128 miles for state-sponsored trains, and 556 miles for long-distance trains.

The Northeast Corridor runs 456 miles from Boston to Washington via Providence, New Haven, New York City, Philadelphia and Baltimore, and is the longest length of track owned by Amtrak. Frequency on the Northeast Corridor is more than 35 round trips each weekday. Additionally, the Northeast Corridor is host to portions of nine commuter railroads: MBTA (Massachusetts and Rhode Island), Shore Line East (Connecticut), CT Rail (Connecticut), Metro-North Railroad (Connecticut and New York), Long Island Rail Road (New York), NJ Transit (New York and New Jersey), SEPTA (New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware), MARC (Maryland and DC), and VRE (DC and Virginia). The Northeast Corridor is the only portion of the nation’s rail system that is even remotely on-par with our peers in Asian and Europe. While service on the Northeast Corridor comes close to breaking even when it comes to operational costs, its capital investment needs have been grossly neglected. While estimates vary, at least $50 billion in investment is needed in order to clear the maintenance backlog and keep the Northeast Corridor in a state of good repair.

Amtrak’s long-distance routes operate almost exclusively on tracks owned and operated by freight railroads. With the exception of two routes that make three trips per week, all long-distance routes operate daily. Long-distance routes vary in length from 764 miles to 2,438 miles. While long-distance routes are expensive to operate, they do provide critical transportation to more than 200 relatively-remote communities around the country. The fleet used to operate the long-distance routes is nearing its operational lifecycle, and Amtrak faces a cost of approximately $10 billion to replace it.

Amtrak’s state-sponsored routes operate almost exclusively on tracks owned and operated by freight railroads. State-sponsored routes vary in length from 86 miles to 704 miles and in frequency from one round trip per day to 16 round trips per day. As the term “state-sponsored” suggests, the capital and operational costs of the state-sponsored routes are paid by the states sponsoring the routes. As such, their continued operation is reliant on state funding rather than federal funding.

Financially, Amtrak finds itself stuck between a rock and a hard place when it comes to deciding whether to put the limited capital funding that it receives into the Northeast corridor or into long-distance trains. Critics frequently target long-distance trains, because the trains feature premium services like sleeper cars and dining cars. However, first-class passengers pay fares that are considerably higher than their peers riding in coach. For example, in 2017 on the California Zephyr, fare yield was 12.8¢ per passenger mile for coach passengers, while first-class fares yielded 24.7¢ per passenger mile. Even when the cost of premium services is accounted for, it still costs Amtrak less per passenger mile for first-class passengers than for coach passengers.

Another attack frequently launched at long-distance trains is that it would be cheaper to fly passengers across the country rather than subsidize them to ride the train. These critics completely miss several key points. As an example, the California Zephyr—Amtrak’s longest route—travels 2,438 miles between Chicago, Illinois and Emeryville (San Francisco), California, and serves 45 stations in seven states. Most of these stations either have limited commercial air service or lack it entirely. Also, this single route with 45 stations yields 1,980 unique station pair combinations, while a direct air route only yields the two combinations. It is also worth noting that the vast majority of long-distance riders do not ride the entire length of the route. For example, barely 10% of trips on the California Zephyr exceed 2,000 miles in length, while half of the trips are 500 miles or less in length.

Criticism of long-distance amenities has prompted Amtrak to conduct an experiment with its dining services. The Silver Meteor and the Silver Star are two long-distance trains running between New York City and Miami on similar routes and similar schedules. For the experiment, which began in 2015, Amtrak has eliminated the dining car on the Silver Star and replaced it with pre-made meals that are microwaved prior to serving to passengers. While I have not heard how the experiment has affected first-class ridership on the Silver Star, I have learned that first-class tickets for the Silver Meteor are typically 20% to 95% more than for the Silver Star.

While Amtrak has weathered numerous budget attacks from Congress, only recently has the threat come from within. In June 2017, former Delta Airlines CEO Richard Anderson was appointed President and CEO of Amtrak. Soon thereafter, rumors of possible changes to long-distance routes started to spread. Chief among the rumors has been elimination of sleepers and dining cars for first-class passengers. Second has been the splitting of long-distance trains into shorter day segments. For example, the 2,438-mile Chicago to Emeryville (San Francisco) California Zephyr would possibly be split into five segments: Chicago to Omaha (500 miles), Omaha to Denver (538 miles), Denver to Salt Lake City (570 miles), Salt Lake City to Reno (594 miles), Reno to Emeryville (236 miles). This would split a continuous 52-hour ride into a 5-day journey requiring separate overnight accommodations in the four intermediate cities. For coach travelers looking for a bargain, the added cost of intermediate accommodations is likely cost-prohibitive.

As a side note, I would support the addition of day trains between those city pairs and a similar service increase throughout the country. However, long-distance trains are still a necessity as long-distance and day trains tend to serve different travel markets.

One of the first changes made by Richard Anderson was the elimination of the Pacific Parlour car on the Seattle to Los Angeles Coast Starlight. From 1995 to early 2008, the Pacific Parlour cars had served as a first-class-only lounge on the Coast Starlight. The cars predated the rest of the Amtrak fleet and were among the oldest equipment still in use by Amtrak. Due to their age, it became increasingly difficult and increasingly expensive for Amtrak to find replacement parts, which provided the justification for their retirement. However, many have objected that the amount of money saved by Amtrak is negligible.

Early in 2018, Amtrak also announced the elimination of chartered train service and chartered private rail cars. In both scenarios, riders would pay Amtrak significant amounts of money to either charter a train outright for private use or to have private rail cars added to the rear end of regularly-scheduled Amtrak trains. Amtrak cited cost-cutting for the change. However, the justification is asinine, since the money paid by riders in both scenarios more than compensates Amtrak for the costs incurred. After numerous complaints were made, Amtrak walked back on changes to chartered private rail cars, although after greatly reducing the number of stations where the private cars can be added and removed from trains.

The next change was the elimination of full-service dining on the Chicago to Washington Capitol Limited and the Chicago to Boston/New York City Lake Shore Limited, which started in June 2018. Akin to the service change on the Silver Star, full-service dining was replaced with pre-made meals that are microwaved prior to serving to passengers. Cost-cutting again provided the justification. And again, many have objected that the amount of money saved by Amtrak is negligible.

The next big change also came in the spring of 2018 with the announcement of major changes to the Chicago to Los Angeles Southwest Chief via Kansas City, Dodge City, Albuquerque and Flagstaff. However, the difficulties faced by the Southwest Chief actually started almost a decade ago.

In 2010, BNSF Railway, which owns the tracks used by the Southwest Chief, informed Amtrak that it would no longer be operating freight trains between Trinidad, Colorado, and Lamy, New Mexico. The change would mean that the full costs of maintaining the 200-mile section of track would fall on Amtrak. With Amtrak’s budget limitations, the future of the Southwest Chief was in jeopardy. However, the states of Kansas, Colorado and New Mexico, along with communities along the route, were able to cobble together funding to cover Amtrak’s increased costs. Everyone thought that the threat had been averted.

The next chapter in the threat to the Southwest Chief actually started 10 years ago in southern California. On Sept. 12, 2008, the engineer operating a Metrolink commuter train passed a red signal and collided head-on with a Union Pacific freight train, killing 25 and injuring 135 in the Chatsworth district of Los Angeles. As a direct result of this disaster, Congress passed the Rail Safety Improvement Act of 2008, which mandated that a sophisticated safety system called Positive Train Control (PTC) be installed on the nation’s railroads by Dec. 31, 2015 with a provision for limited exceptions, which we will return to in three paragraphs. This requirement by Congress was an unfunded mandate, which left both freight railroads and especially taxpayer-funded passengers railroads struggling to figure out how to pay for. Due to the cost and time required to comply with the mandate, the deadline to implement PTC was pushed back to Dec. 31, 2018.

To summarize PTC, Union Pacific has produced a short summary video. The key takeaway from the summary: “If the engineer does not react to instructions in a timely manner, PTC fully engages the locomotive’s brakes stopping the train before an accident can occur.”

On Dece. 18, 2017, an Amtrak Cascades train derailed near DuPont, Washington, killing three and injuring 62. Two of the fatalities were colleagues of mine from the Rail Passengers Association. While the direct cause of the disaster was operator error, it was evident that the crash could have been averted had PTC been operational. The crash promoted Richard Anderson—in the months following—to announce that Amtrak would stop running trains on sections of tracks lacking PTC after Dec. 31, 2018.

While safety is of utmost importance, PTC is an expensive solution for infrequently used sections of track, and there are other ways of ensuring the same level of safety at lower cost in those situations. The Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) can approve alternative safety measures in limited circumstances by granting a Main Line Track Exclusion Addendum (MTEA). For example, if a section of unsignaled track serves four or fewer trains per day or if a section of signaled track serves 12 or fewer trains per day and alternative safety measures can be implemented, the FRA can grant an MTEA to exclude the track from the PTC requirement.

Details of the proposed changes to the Southwest Chief emerged in August 2018. Amtrak officials gave presentations in communities along the route of the Southwest Chief. Multiple alternatives were evaluated; however, Amtrak seemed to have settled on replacing the 565-mile section of the route between Dodge City and Albuquerque with bus service. Also included in the proposed changes is the removal of sleeper cars and dining cars from the Southwest Chief.

Their justification for the change can be broken down by three sections of track: 1. The 283-mile segment of track between Dodge City and Trinidad owned and operated by BNSF does not carry enough rail traffic to necessitate the installation of PTC, and BNSF has been granted an MTEA by the FRA to exclude the track from the PTC requirement. However, Richard Anderson’s mandate that all Amtrak trains operate under PTC would require capital costs of $30 million in order install PTC. That full cost would fall on Amtrak (rather than being shared with BNSF), because Amtrak is requiring it rather than the FRA. 2. The 200-mile segment of track between Trinidad and Lamy owned by BNSF—which now only carries the Southwest Chief—does not carry enough rail traffic to necessitate the installation of PTC, and BNSF has been granted an MTEA by the FRA to exclude the track from the PTC requirement. This is the same section of track mentioned earlier, the maintenance of which now falls exclusively on Amtrak. Despite the MTEA granted by the FRA, Richard Anderson’s mandate that all Amtrak trains operate under PTC would require capital costs of $23 million in order install PTC. 3. The 82-mile segment of track between Lamy and Albuquerque owned by the New Mexico Department of Transportation (NMDOT)—which carries the Southwest Chief, Rail Runner commuter rail trains and local freight trains—will require the installation of PTC. However, as NMDOT will not meet the deadline for PTC installation, it is in the process of applying for an MTEA and will reduce rail traffic on the segment to comply with the MTEA until PTC can be installed. Additionally, it is important to note that terminating the Southwest Chief at Dodge City and Albuquerque will require as much as $13 million in capital funding for maintenance and layover facilities in Dodge City and Albuquerque.

Simply stated, the changes proposed by Amtrak—under Richard Anderson’s leadership—are nonsensical. They mirror the sneaky tactics employed by railroads prior to the creation of Amtrak to justify discontinuing routes. Amtrak is imposing requirements and costs on itself that aren’t actually mandated by the Federal Railroad Administration. Statistically-speaking, passengers are safer riding on 565 miles of non-PTC tracks than they are riding the replacement bus for 565 miles. There is also no justification given for the removal of sleeper cars and dining cars from the Southwest Chief.

While Amtrak has made no announcements regarding how Richard Anderson’s PTC mandate would affect other routes, Trains magazine was quick to compile a list of seven other Amtrak routes that would be operating on sections of track without PTC under MTEAs granted by the FRA. The California Zephyr is on that list due to a 152-mile section of lightly-trafficked track between Grand Junction and Helper, for which Union Pacific has obtained an MTEA from the FRA. Consistency would necessitate applying the same thinking applied to the Southwest Chief to the California Zephyr.

Amtrak released a statement that might suggest it’s considering walking back on its PTC mandate. Until Amtrak uses more convincing language, the Rail Passengers Association will continue to press Congress for legislation requiring Amtrak to preserve its national network.

Speaking of my own travel preferences, I enjoy traveling around the country on Amtrak. I am willing to spend more time and money getting to destinations, so that I can experience the countryside and mingle with my fellow travelers. However, I am unlikely to continue to travel long-distances on Amtrak if stretches of routes are replaced with buses and if the first-class amenities of sleeper cars and dining cars are removed from trains.