Press Release

Welcome to the Beehive Archive—your weekly bite-sized look at some of the most pivotal—and peculiar—events in Utah history. With all of the history and none of the dust, the Beehive Archive is a fun way to catch up on Utah’s past. Beehive Archive is a production of Utah Humanities, provided to local papers as a weekly feature article focusing on Utah history topics drawn from our award-winning radio series, which can be heard each week on Utah Public Radio.

The Energy Transition Powered by Rural Utah

When you flip your light switch, do you know which part of rural Utah your electricity is coming from? Historically, fuel for the energy grid came from rural areas in the form of fossil fuels. But even as utilities transition to alternative energy, that energy is still sourced in rural Utah.

Coal-fired power plants became the dominant source of electricity in Utah in the late twentieth century. Because coal mines, almost by definition, exist in rural places, Utah’s cities have long been powered by a rural product. A shift toward renewable energy has changed the way we produce electricity, but rural places are still responsible for most of our power.

What we now think of as “alternative energy” was actually the precursor to coal-fired power. While coal was used as fuel in industrial processes in the nineteenth century, it was actually hydropower turbines that were the state’s first electrical generators. As the state’s electrical capacity increased through the 1920s — mostly by building hydropower dams — residential homes in cities began electrifying. Electrification in rural areas was a slower process, however, even though dams in rural areas were providing all the power.

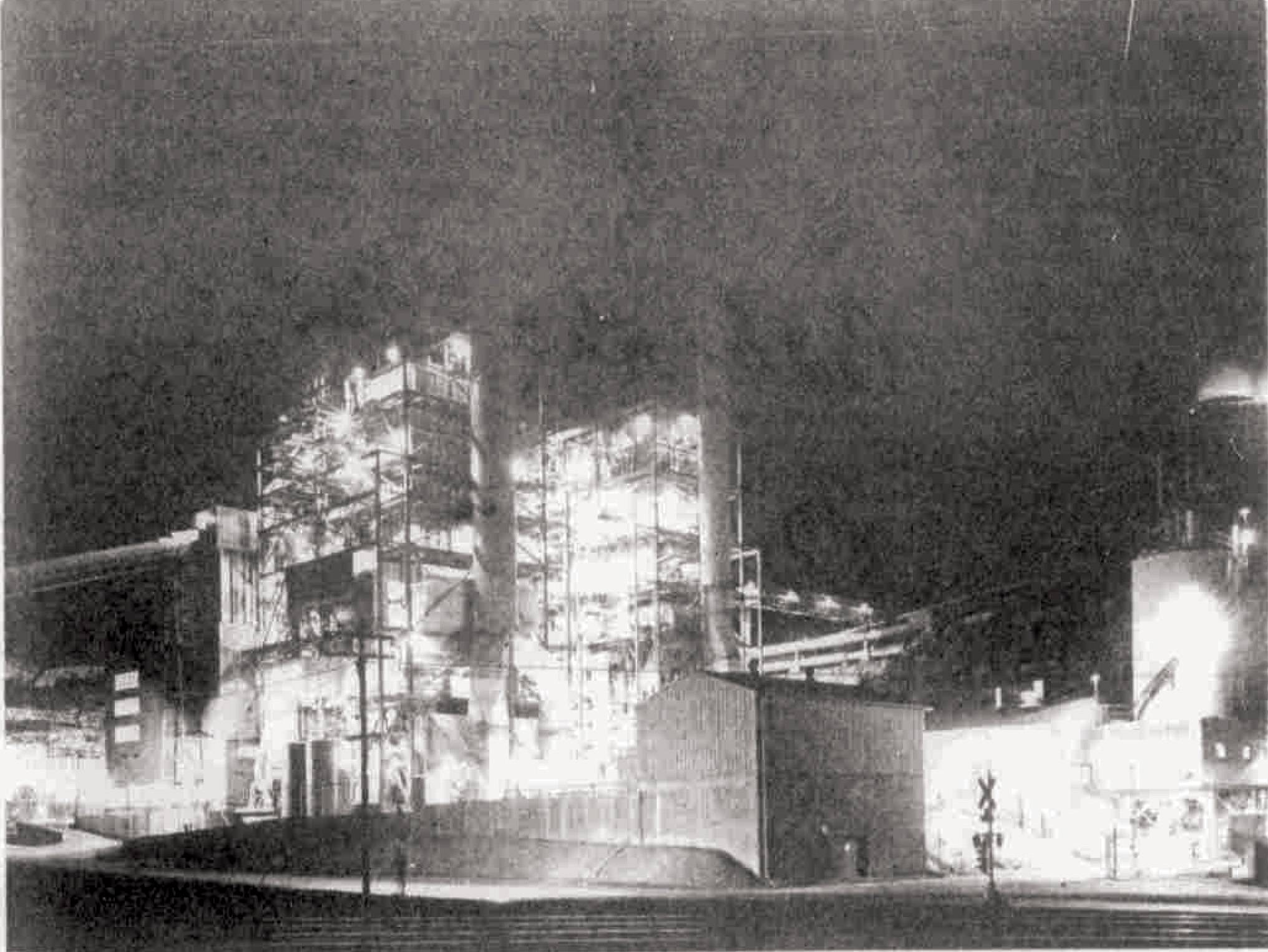

In 1954, the Utah Power & Light Company built a coal-fired power plant in Carbon County. It was a signal of things to come. As recently as the year 2000, coal provided 94% of Utah’s electricity. Since then, a combination of diminishing coal reserves, enhanced environmental regulations, and concern about global warming have contributed to a transition away from coal. In its place, new technology has made it possible to generate power from several other sources. For example, geothermal energy harnesses the heat from naturally occurring volcanic activity. Milford, in Utah’s west desert, is home to an experimental field site known as FORGE dedicated to researching geothermal energy. Although Utah does not have any nuclear power plants, uranium mined in Utah is used as fuel. Then there are contemporary wind farms built in places with steady wind currents that now provide renewable energy in several of Utah’s counties. While windmills in the nineteenth-century also provided power – it was to pump groundwater, not generate electricity.

In the past, and today, rural communities have depended on jobs from coal mining and the extraction of other fossil fuels. As coal deposits run out, those communities are in a tough spot. The energy transition may provide a silver lining, however, as alternative sources are still located in rural areas around the state. Living in rural Utah has always required the ability to adapt, and the energy transition is no exception.

Beehive Archive is a production of Utah Humanities and its partners. Sources consulted in the creation of the Beehive Archive and past episodes may be found at www.utahhumanities.org/stories. © Utah Humanities 2024